CONTENTS

About Mikadoya

Concept

Set in Tsuwano, a town often called the “Little Kyoto” of San’in, Mikadoya is a fully Japanese-style standalone house converted from a former ryokan (traditional inn). Built in 1953 (Showa 28), the building preserves craftsmanship throughout—timber joinery, transom panels, and more—creating a space that feels as if time has gently come to a halt.

The culinary pillar here is wild ayu (sweetfish) from the pristine Takatsu River—often called the finest in Japan. Fish are procured exclusively from the stretch between Nichihara and Yokota, and prepared with restrained, meticulous techniques that draw out their fragrance and flavor to the fullest . In addition to an all-ayu tasting, there are seasonal courses such as soft-shelled turtle (suppon) and wagyu kaiseki, with menus that honor the ingredients of each season.

The Takatsu River has no dams and has been selected multiple times as “Japan’s cleanest” among first-class rivers. Ayu that graze on moss nurtured by its crystal-clear flow have an exceptional aroma and umami .

The Chef (Ichiro Yamane)

Ichiro Yamane, the third-generation chef, hails from Tsuwano. After graduating from the local high school, he trained around Japan and returned at 25 to take up the counter at Mikadoya.

In 2023 he appeared on TBS’s “Jonetsu Tairiku” (Passion Continent), introduced nationwide as a chef who knows the Takatsu River’s ayu inside out . His salt-grilled wild ayu, cooked with reverence for the region and the fish, is deceptively simple yet makes connoisseurs swoon.

Through his cooking, he conveys the nature of the Takatsu River and the culture of the town—an ethos that embodies the pride of a truly community-rooted restaurant.

About the Fourth Generation

After training at Kyoto’s renowned “Ogata,” the fourth generation has now returned to Tsuwano to work at Mikadoya. As the son of the third-generation chef, Ichiro Yamane, he has already begun taking the field.

While bringing in the poise and sensibility honed at Ogata, he carefully preserves flavors rooted in this land. His respect for ingredients—foremost the wild ayu of the Takatsu River—and his work that pares flavors to their clean contours reveal a sense of responsibility and resolve beyond his years, befitting an heir.

In the kitchen, his rhythm with the third generation is natural. With few words exchanged, their hands move, and each plate flows to completion. It remains a family business—unpretentious yet carefully inherited—and that air carries straight into the food.

In his choice of vessels and composition, you occasionally glimpse the sensibilities cultivated at Ogata, but they never dominate. It is unmistakably Mikadoya’s flavor, seamlessly woven into Tsuwano’s own timeline.

With the young fourth generation now on board, Mikadoya today radiates both the quiet confidence built up over generations and an open margin for what is to come. You can feel that “succession” and “renewal” have already begun.

Restaurant Accolades

Though located in the small town of Tsuwano in Shimane, Mikadoya’s name carries clear weight within the culinary world.

In recent years in particular, its consecutive wins at the Tabelog Awards speak to that credibility. Silver in 2025, Bronze in 2024, and oscillating between Silver and Bronze in prior years—its evaluations remain steady. The number of guests who travel long distances to dine here reflects that standing.

It has also been selected multiple times for the “Tabelog Top 100 Japanese Restaurants – WEST.” The fact that it appears alongside Tokyo and Osaka as a restaurant supported by chefs and gourmets nationwide is significant. It shows the ability to compete on the same stage as top urban restaurants.

Furthermore, in the French guide “Gault&Millau,” it has been introduced with a high score of 16/20, so the recognition is not limited to Japan. Anchored in the blessings of its land, yet with a sharpened menu structure, thoughtful use of tableware, and the ability to beautifully compose even the “silences” of flavor—these strengths clearly reach external evaluators.

Among word-of-mouth reviews, the all-ayu course is the most discussed. Many express surprise—“Who knew grilling ayu alone could express so much”—and there are many repeat diners who say, “I want to visit once a year,” noting that from grilled fish to uruka (salted, fermented ayu entrails) to ayu rice, the course never wavers from start to finish.

Particularly praised is the uruka as a delicacy and its pairings with local sake. It’s not just about great ingredients; the course design that evokes taste memories as a whole is highly regarded.

Looking at the awards and firsthand reviews, you realize Mikadoya’s appeal lies not in “flashy innovation” but in “continuity of place and craft.” Even while earning national accolades, there is no unnecessary embellishment or theatrics—only a quiet accumulation of deliciousness.

It is precisely that quietness that feels like the restaurant’s greatest strength.

Dining Prelude

Exterior & Entrance

Mikadoya’s exterior blends into the townscape of Tsuwano. While the building clearly retains the character of the former ryokan, it now wears the air of a kappo (fine Japanese dining house).

The front wooden gate stands in solid, unadorned timber, with a single quiet blue noren (shop curtain) hanging above. Though facing the street, it makes no show of its presence—an attitude that seems to embody the restaurant itself.

A signboard under the eaves still reads “Ryokan,” a vestige that quietly speaks to the depth of the years this place has been rooted here.

A tank by the entrance holds wild ayu from the Takatsu River, wordlessly telling visitors what lies at the heart of the cuisine. The entire building gently envelops a sense of “time that can only be savored here,” and even before stepping inside, expectation and calm coexist.

It captivates not with bustle but with restraint. That quiet pull betrays the restaurant’s essence.

Dining Space

Just as the exterior is calm and understated, the interiors are wrapped in a dignified air free of excessive staging.

We were shown to a tatami-matted private room. In the quiet tokonoma (alcove) beyond the sliding door hung a scroll and a small single-stem arrangement. The unforced seasonal accents gently eased the formality of the dining setting.

With the soft light filtering through shoji, the whole space feels designed as part of the meal. The ceiling is low; the walls are divided into subdued green and white; though fitted with chairs, the room retains the tranquility of a washitsu (Japanese-style room).

Rooms are separated by fusuma and can be opened to change the size as needed. The only sounds are the clink of tableware and low voices. One realizes that here, time is meant to be savored not in liveliness but in quiet.

A stillness that doesn’t interfere with the ingredients’ aromas or lingering finish—as if the room itself were waiting for the dishes to begin speaking.

Menu Presentation

Mikadoya serves a single omakase course that changes significantly with the seasons. In July, the composition becomes an “all-ayu” course centered on wild ayu from the Takatsu River.

From appetizers to the final rice, the course consistently lets you experience ayu from many angles. While the exact lineup shifts with that day’s sourcing, the backbone typically looks like this:

Mikadoya’s Course Structure Through the Year

At Mikadoya, there are two distinct omakase formats: the Ayu Season (June–end of September) and the Off-Season (October through spring).

● Ayu Course (June–end of September)

An “all-ayu” course with wild fish from the Takatsu River at its core.

-

Begins with se-goshi (paper-thin raw slices cut bone-in from the back). It may be served as arai (lightly washed sashimi) instead.

-

Around 10–11 items in total: winter melon and ayu in a clear soup; salt-grilled ayu; ayu with sansho soy; simmered dishes with uruka (salted, fermented ayu entrails) and eggplant; vinegared ayu; fried ayu; and more.

-

Finishes with ayu rice; shaved ice with candied green ume may appear for dessert.

-

Price range is roughly ¥11,000–¥16,500 (tax included), varying with supply and content.

● Off-Season Kaiseki / Seasonal Ingredients Course (October–end of May)

During the closed season for ayu, the menu shifts to kaiseki featuring seasonal produce and local specialties.

-

From October you may find a “Lightly Grilled Roe-Bearing Ayu” course (around ¥33,000) and a Matsutake & Roe-Bearing Ayu Course (around ¥55,000).

-

In winter–spring they also offer a wild suppon (soft-shelled turtle) course (around ¥33,000), fugu (pufferfish) courses (farmed from ¥16,500 / wild from ¥33,000), a flower sansho & Shimane wagyu course (from around ¥33,000), and comparison courses of wild game such as bear/boar with Shimane wagyu (from around ¥41,800).

-

From December to May, a standard kaiseki (centered on Shimane wagyu and local vegetables) is offered in the ¥11,000–¥16,500 range.

Starter Drink

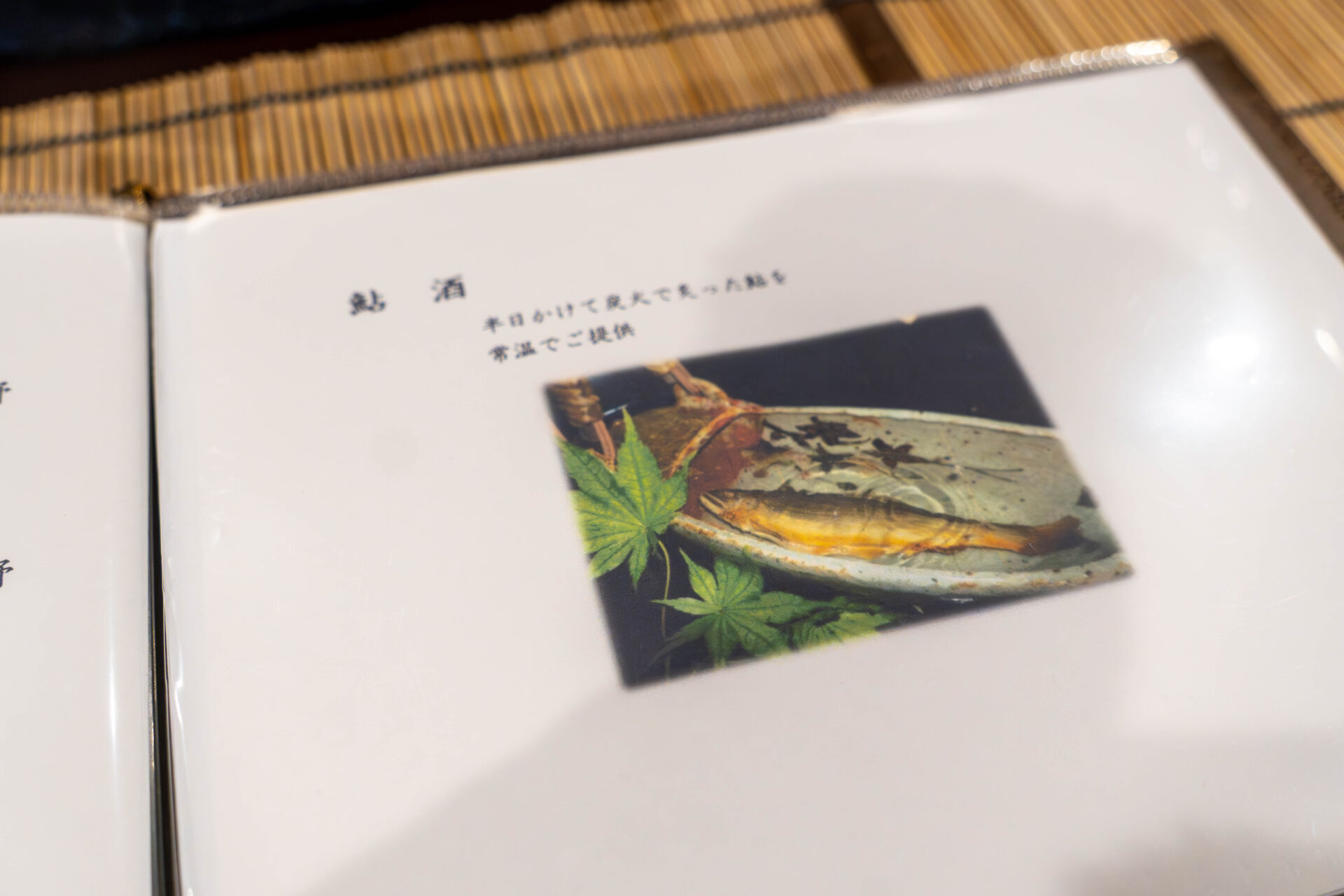

On this day, we chose “ayu-zake” (ayu-infused warmed sake). A whole grilled ayu is submerged, releasing a roasty aroma and a gentle bitterness from the innards that lingers.

It feels less like “just sake” and more like a dish of ayu in its own right. It flowed naturally with the progression of the meal.

Dishes We Tasted

Ayu “Nanban” Congee

Crisp-fried ayu that had been marinated “nanban” style, combined with a porridge-like glossy sauce. Though called congee, there are no distinct grains; the silky sauce gently enrobes the fried ayu with acidity.

Some bones remain for texture; alongside the toasty aroma of the fry, you feel the firmness of the fish. The more you chew, the more umami emerges—exacting work. The faint sweetness and acidity of the “congee” stay in balance, and each bite comes together on the palate.

Served on glassware with cool transparency—a plate that quietly ushers in summer ayu.

Ayu & Winter Melon Soup

A bowl pairing a grilled half of ayu with tender simmered winter melon. A hint of char drifts into the clear dashi, and the fragrance that rises the moment you lift the lid is striking.

With the grilled side left on, the ayu balances crispy skin and moist flesh, pairing gently with the dashi-soaked winter melon. Neither element is assertive, yet both leave a sure impression—an elegant harmony of ingredients.

The vessel is silver-toned metal—slightly modern in feel—yet it traps heat well, so the rush of heat and aroma when opened is pronounced. As a bowl “to seal in and deliver” ayu’s aroma, it feels perfectly logical.

Placed mid-course, it creates a pause—of aroma, temperature, and breath—before moving on.

Ayu Se-goshi (Bone-in Thin Slices)

Laid as if hidden at the bottom of a bowl packed with ice, the se-goshi of ayu is lifted piece by piece from the ice and dabbed dry with paper before eating.

Cut raw and paper-thin with the bones, the ayu is astonishingly smooth on the palate, its aroma pristine.

That this dish works as se-goshi is precisely because it’s ayu from the Takatsu River.

Only with the purity to be eaten raw and the knife skills to slice it bone-in does the plate come together.

A quiet dish in which the power of the ingredient and the certainty of technique come through naturally.

Whole Grilled Ayu

The grilled ayu served was on the smaller side. In this season, aroma stands out more than fattiness; the char on the skin and the taut flesh were memorable.

The grill was not overly strong: skin crisp, flesh gently plump. The size worked to advantage, making the aroma especially pleasant.

The accompanying tade-zu (water pepper vinegar) had restrained acidity and green notes, lifting the ayu’s flavor without getting in the way. Salt and fire alone complete the dish, and the faint acidity resets the palate once more.

It was a fitting first whole-grilled fish, showcasing the way smaller ayu release their fragrance.

Ayu Spring Roll

Presented wrapped in paper and handed directly to you by the attendant. The heat is evident the instant it’s passed over—surprisingly hot. The skin is fragrantly crisp, and when you bite in, the aroma of ayu and uruka miso billows out.

Inside is flaked ayu with a gentle touch of uruka miso. It has depth but isn’t heavy, preserving the lightness of a spring roll. As you eat, fragrant whole sansho berries appear toward the bottom, leaving a refreshing afterglow that resets the palate.

There’s a clearly designed progression of flavor—flow within a single bite. It’s also striking how it stays hot to the end, hinting at the precision of the frying and wrapping.

Not a filler but a dish with a defined role in the course. Ingredient, composition, and technique all lock cleanly into place.

Grilled Ayu (Second Serving)

Next came a slightly larger ayu than the first. The added thickness made not only the roasted aroma but the fish’s own flavor and texture more distinct.

The grilling remained careful: skin crisp and fragrant, inside moist. The pleasant bitterness and umami of the innards also came through, the fish’s maturity showing directly in flavor.

It was a serving that sharpened the outline of ayu itself. The size difference reads as a deliberate intention—more than repetition, it’s a progression.

Ko-Uruka (Salted Ayu Roe)

We added “ko-uruka”: roe from ayu caught in late autumn on the Takatsu River, salted while still white-egg stage, then matured and fermented as is.

Among Japanese chinmi (rare delicacies), this has a relatively clean mouthfeel. It’s well-seasoned with umami yet not overly funky—easy to enjoy even without sake.

Chilled and glistening in a glass bowl, it felt like out-of-season ayu given a new life through preservation and the passage of time.

Simmered Course: Eggplant with Uruka

Served with the final rice was eggplant simmered in uruka. Made from salted and fermented ayu entrails, uruka carries profound umami and a gentle bitterness that penetrates the eggplant’s tender flesh.

There are no extraneous flavors in the broth; fermentation-driven savoriness rises softly. Drop some white rice into the remaining liquid and the rice’s sweetness mingles with the fermented depth—satisfying to the last bite.

The course explores not only ayu itself but ayu as a seasoning. These multifaceted “ways of tasting ayu” appear throughout, making the composition particularly memorable.

Palate Cleanser: Vinegared Ayu

A cool vinegared dish served after the grilled and fried courses.

The lightly pickled ayu has a moist texture and draws out the sweetness hidden deep in the flesh, aligning quietly with a gentle vinegar.

Cucumber’s crunch and yam’s refreshing clarity lend juiciness overall, revealing another side of ayu.

Rather than simply resetting the palate, it tidies the arc so far and creates space for what follows.

Ayu Rice with White Miso Soup

For the finish: ayu rice generously mixed with flakes of fragrantly grilled fish.

Moist flesh and toasty skin permeate the grains; the more you chew, the more ayu’s aroma spreads. The seasoning is gentle—balanced so you never tire of it.

Paired white miso soup has a soft sweetness and mellow roundness, gently settling the meal’s afterglow.

A calm conclusion befitting the course—respect for the ingredient runs through to the end.

Candied Green Ume

Dessert was shaved ice hiding candied green ume.

Beneath the ice was a plump, gently simmered green ume.

Its sweetness reached the core while its tartness and aroma remained, leaving a refreshing finish.

The condensed ume flavor combined with cool ice—a perfect close that evoked the end of summer.

Summary & Impressions

The Takatsu River flows through Tsuwano.

To taste wild ayu raised in its clear waters, prepared by chefs over three generations—

it felt less like a meal and more like “eating a landscape.”

In this quiet place enclosed by mountains and within earshot of the river, the lives of people who live with nature rise from each plate.

When you flake the fish, you imagine the time that flowed within it and even the river’s scent.

That comes not only from the rare power of the Takatsu River but from the family who has faced ayu here for generations.

What you feel from the third-generation chef’s hands is not just technique and knowledge.

It’s a resolve and reverence for handling ayu in this land—and a will to deliver “something that can only be eaten here and now.”

What’s served in the vessels is more than “food.”

The quiet, beauty, and modest pride of Tsuwano—

even that atmosphere gently seeps in with each bite.

The considerate, understated hospitality is another charm of this place.

There’s no over-explaining or pushiness, yet watchfulness is constant; the distance that leaves space to the diner feels right.

It was time that touched an original landscape—something cities can never reproduce.

The feel of the seasons and the land’s memories speak quietly through the form of cuisine.

It made me feel that true “luxury” resides there.

Reservations & Access

How to Book

-

Advance reservations required. Bookings are accepted by phone only (for parties of 2 or more). Reservations for a single diner are not available.

Calling early to check availability for your preferred date is the most reliable. -

They may occasionally accept via some platforms such as Pocket Concierge, but phone reservations are most reliable.

Hours & Regular Holidays

-

Hours (last seating for each):

• Lunch: 12:00–13:00

• Dinner: 17:00–19:00 -

Some sources list a start at 11:30; as there are discrepancies, it’s safest to confirm by phone.

-

Closed: Mondays and August 14–16 for summer holidays

Access & Location

-

Address: 221-2 Nichihara, Tsuwano-cho, Kanoashi-gun, Shimane Prefecture

-

Nearest transport:

• 15–21 minutes on foot from JR Yamaguchi Line, Nichihara Station; 3–5 minutes by taxi

• About 25–30 minutes by car from Hagi–Iwami Airport -

Parking: Available (6 spaces)

Best Time to Visit

-

Ayu Course Season: The best time to savor ayu at peak richness is June to around the end of October. If you want to focus on summer Takatsu River ayu, this period is ideal.

-

Best for sightseeing in Tsuwano: October–November offers chances to see a “sea of clouds” (unkai) from the Tsuwano Castle Ruins; pairing that scenery with dining makes this season especially recommended.

-

- TAGS